The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) recent COVID-19 changes to it’s Alternative Payment Models (APMs) present an opportunity for the oncology community. With the changes, CMS has given Oncology Care Model (OCM) practices the opportunity to “forgo upside and downside risk for performance periods” during the pandemic, to remove COVID-19 related episodes, and to elect into aggregate quality measures. However, the biggest win one could argue was extending the model through June 2022.1

While some might not see this as an opportunity, given the mixed reviews of the success of OCM, this extension allows the community more time to evaluate and understand CMS’ newest iteration of value-based oncology proposed in November of 2019- the Oncology Care First (OCF) model.

For OCF to be successful, it is clear the oncology community feels reform to value-based oncology is needed. But, the question that remains is:

Would this new model actually address the underlying concerns within OCM?

To foster dialogue around this question, CareJourney projected payments under the new OCF criteria. Fill the form to see the breakdown for your practice groups of interest.

The Challenges With OCM

In beginning to understand the potential of OCF, it is important to review the challenges the oncology world feels with OCM. At a high level, OCM, which began in July of 2016, is a CMS payment model targeting oncology practices in an effort to better serve Medicare beneficiaries. The model was scheduled to end in June of 2021; however, with the recent global pandemic, CMS has extended OCM until June of 2022.2

By participating in the model, oncology practices strive to improve quality of care for their patients, as well as provide enhanced oncology services (also outlined by CMS). Payments within OCM provide practices with a monthly payment designed to cover the expenses of the mandated oncology care practice patterns, as well as a performance-based payment aimed to incentivize improving quality while reducing costs across cancer episodes.3

While the foundations of the model align with the overall oncology community’s commitment to value-based care, there are a few pieces of the model that received feedback across the past years.

There are initial costs and burdens in building practice group infrastructure for OCM.

Across participants, many practice groups have mentioned the costs they incurred to train up their staff on the new model and develop the internal infrastructure to coordinate care. Like many new things that require investment, this is not unheard of. Yet, in reviewing the model, practices also frequently note extensive reporting criteria for model participants, particularly around the labor of aggregating quality metrics from multiple sources and places.4

OCM’s payment structure does not reflect the current state of novel treatment prices.

Since OCM was introduced in 2016, it’s payment structure is founded on claims data before 2015. With the vast changes to oncology treatments between 2015 and 2020, many practices feel the pricing structure of the model does not accurately take into account the pricing treatment offerings that have been introduced more recently. As a result, some practices feel there is a penalty for using more current treatments that are sometimes more expensive.5

Many practices struggle with the attribution of patients.

For many of the CMS payment models, the number of attributed patients is a key factor. In OCM, oncology practices have expressed a variety of challenges around attribution. For example, to identify the number of attributed patients, practices can look to see which patients have received chemotherapy. However, this is much more complicated for patients who are receiving oral chemotherapy. Additionally, many practices hope for reform to the monthly payment attribution process.6

With this feedback in mind, CMS introduced the new model, OCF, colloquially referred to as OCM 2.0.

How does the Oncology Care Model work?

Oncology Care First (OCF), similar to the CMS’ OCM, is another model intending to promote coordinated, holistic oncology care for patients while reducing overall costs. The model is available to physician group practices or hospital outpatient departments.

Similar to OCM, to participate in the model, practices must7:

- “Offer beneficiaries 24/7 access to a clinician with real-time access to their medical records;

- Provide the core functions of patient navigation;

- Document a care plan for beneficiaries that contains the 13 components of the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) Care Management Plan;

- Treat beneficiaries with therapies consistent with nationally recognized clinical guidelines;

- Use Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) as specified in regulation;

- Utilize data for continuous quality improvement; and

- Gradually implement electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePROs).”

The OCF model combines both upside and downside risk for it’s oncology practice groups and offers 3 risk tracks: (i) upside risk, (ii) downside risk, (iii) blending of other two risk tracks. For any practices transitioning from the sunsetting OCM model to OCF, there is a requirement to take on downside risk to participate. Other practices dipping their toe into the water of value-based oncology are eligible for a one sided risk track for a defined period of time as they grow accustomed to the model.

In terms of the payments, OCF provides two types of payments for members.

- The first is the Monthly Population Payment (MPP). This is a fixed capitated payment that provides OCF practices a set sum for E&M services rendered by a medical oncologist. This sum is calculated based on the practice’s full Medicare population and includes patients who are treated with chemotherapy and those that are not.

- The second is the Performance Based Payment (PBP). This payment mirrors the performance payments in OCM. The payment holds OCM practices responsible for the total cost of care (including drugs) across a patient’s six-month episodes. With this payment, if practices see total costs of care below the benchmark (both from a cost and quality perspective), then they receive the PBP. On the other hand, if practices exceed the benchmark, then they owe CMS a PBP recoupment. For the PBP, an episode is triggered by chemotherapy and only applicable for beneficiaries enrolled in Part B or Part D Medicare fee-for-service.7

See Deeper OCF Analysis

Go to our live data dashboard to see projected payments under the new OCF criteria using 2019 Medicare Claims data.

The Impacts of OCF

While there are many similarities between OCM and OCF, there are also a few key distinctions. An article in the National Law Review mentioned three of the main ones;

OCF expands the number of eligible beneficiaries for practices.

This is a significant change. Previously in OCM, beneficiaries were limited to patients who were receiving chemotherapy. This was also further complicated by the challenge around understanding when patients received oral chemotherapy (as mentioned above). While the calculation is still a bit uncertain for the MPP, in OCF, it is understood that the beneficiary criteria for the MPP is much more extensive than OCM. In fact, the payment will be calculated based on patients who are treated with chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or without cancer drugs – a significant departure from the former model.8

OCF simplifies OCM’s historical MEOS payment into one simple MPP.

In addition to the critiques above, many felt that OCM lacks transparency for the payment calculations and that the process is too complicated. The OCF model aims to simplify the calculations for the MPP into one prospective payment with no special retrospective FDA carve out, like in OCM. When taken into account across OCF’s expanded definition of attributable beneficiaries, this has the potential to significantly change things for practices.

OCF incorporates cancer type into the novel drug adjustment.

Another big change for the OCF model targets some of the feedback around the novel drug therapy prices. Specifically, OCF will now take into account cancer type when calculating the novel drug adjustments. This is impactful for practices, as drug prices can vary by cancer type.9 This sensitivity will allow for those practices that commonly deal with the high cost cancer medications to also participate in the model.

Assessing OCF

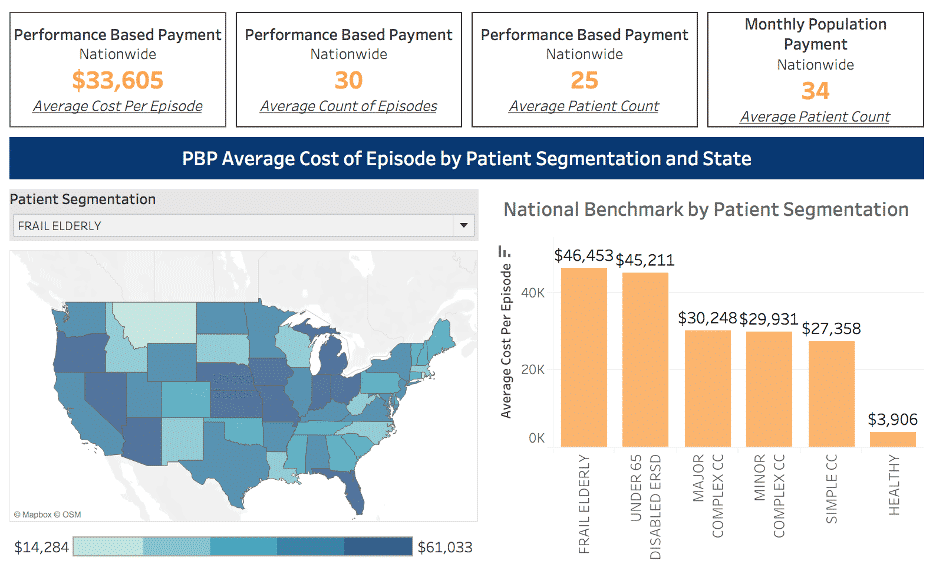

To further assess the impacts of the OCF model, CareJourney projected payments under the new criteria for 2019 as a point of reference. These are available by geography in the dashboard linked above for both the PBP and the MPP. However, a few interesting takeaways on the PBP are summarized below.

OCF PBP episode payments differ by state, but this does not appear to be related to the state’s total number of episodes.

Looking on the state level for 2019, Missouri and Kansas would have had the highest average PBP per episode cost with a total of $42,957 and $42,843, respectively. On the other extreme, Rhode Island and the Virgin Islands would have had the lowest per episode cost of $8,559 and $4,097, respectively.

| State | Count PBP Episodes | Total Number of Patients | Average PBP Episode Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| MO | 10,891 | 9,895 | 42,957 |

| KS | 6,240 | 5,366 | 42,843 |

| FL | 46,181 | 40,188 | 42,501 |

| OH | 9,480 | 8,178 | 42,058 |

| NE | 5,295 | 4,533 | 41,839 |

| AZ | 13,831 | 12,303 | 40,991 |

| MI | 8,863 | 7,654 | 50,514 |

| ND | 797 | 687 | 39,696 |

| IN | 8,662 | 7,425 | 39,571 |

| AK | 1,811 | 1,660 | 39,194 |

Chart 1: Applying the OCF PBP Calculations to 2019: A State by State Breakdown

Additionally, across the top 10 states that would have had the highest PBP average episode cost, there is a range of PBP episode volume. Some states see quite a significant number of episodes, while others see very few. In fact, across all states, the average per episode cost and number of episodes do not end up being strongly correlated (a correlation of 0.31 for 2019 on the state level and a correlation of -0.05 on the provider level). Furthermore, the average per episode cost is also not strongly correlated (0.43) with whether or not the attributed provider participated in OCM.

This is somewhat surprising given the infrastructure investments to support oncology value based care. One might think that after making those investments (for providers participating in OCM or states with high volume oncology episodes), there would be a stronger correlation with a reduction in average per episode costs.

With this in mind, a key question for OCF will be how to incentivize scaling oncology value-based care.

OCF PBP episode payments differ by frailty segmentation.

In further assessing these PBP payments, the frail elderly patients lead other patient segments in the highest costs for PBP episodes across 2019. This aligns with CareJourney’s analysis of the Ashish Jha High Needs, High Cost segmentation overall with the frail elderly patient segment typically experiencing high spend relative to their overall volume.

| Volume in 2019 | Cost Per PBP Episode | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Need, High Cost Patient Segment |

Count of PBP Episodes Nationally |

Number of Patients Nationally |

2106 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Frail Elderly | 91,280 | 78,790 | $41,356 | $43,328 | $45,248 | $46,453 |

| Under 65 Disabled ERSD | 30,429 | 26,556 | $41,856 | $44,131 | $45,693 | $45,211 |

| Major Complex CC | 274,331 | 230,317 | $27,691 | $28,850 | $30,448 | $30,248 |

| Minor Complex CC | 89,782 | 74,265 | $26,600 | $27,972 | $29,878 | $29,931 |

| Simple CC | 66,160 | 54,913 | $25,868 | $26,867 | $27,855 | $27,358 |

| Healthy | 3,426 | 2,514 | $3,180 | $3,244 | $3,166 | $3,906 |

Chart 2: Applying the OCF PBP Calculations to 2019: Looking by Frailty Segment

Yet, in looking across the different segments, it also stands out that the frail elderly segment experiences less Part B spend and more inpatient spend, as seen below. This begins to also prompt the question:

Within OCF, does the frail elderly population need a different care approach when compared to other patient populations?

| High Need, High Cost Patient Segment | Average of Cost Per PBP Episode | Average Yearly Part B Allowed Amount | Average Yearly Inpatient Allowed Amount | Average Yearly Outpatient Allowed Amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frail Elderly | $46,453 | $750,970 | $345,025 | $106,806 |

| Under 65 Disabled ERSD | $45,211 | $543,584 | $179,062 | $185,758 |

| Major Complex CC | $30,248 | $908,244 | $164,022 | $124,480 |

| Minor Complex CC | $29, 931 | $619,515 | $59,363 | $71,696 |

| Simple CC | $27,358 | $539,314 | $37,278 | $59,158 |

| Healthy | $3,906 | $64,724 | $17,227 | $10,024 |

Chart 3: Applying the OCF PBP Calculations to 2019: Looking by Frailty Segment

Explore with CareJourney

In the short time since the release of the OCF request for information, the oncology community and stakeholders have actively engaged in communication with CMS to refine the model.10 With the extension of the OCM for an additional year due to COVID-19, the community now has more time to engage with CMS, understand the exact methodology behind OCF, and the intricacies of its differences from OCM some of which are mentioned above.

As of September 2019, there were 175 practices and 10 payers participating in OCM. A question on many people’s minds now is:

How many practices will enter into OCF?

While that remains to be seen, CareJourney is committed to continuing to assess the new model using our longitudinal 100% FFS claims data set.

CareJourney looks forward to continuing the conversation around OCM and OCF with our members as the oncology community continues to move toward value-based care.

In the pursuit of value based oncology, CareJourney will partner with members to:

- Think critically of definitions for high performing oncology practice groups and providers from both a cost and quality perspective;

- Benchmark episodic performance by geography and cancer type;

- Sustainably grow oncology networks using CareJourney Provider Performance Index metrics, as well as supplemental data;

- Evaluate cancer referral patterns;

- And assess geographic variations in oncology care.

For those considering the impacts of CMS’ oncology models and value-based oncology more broadly, we would love to hear from you at jumpstart@carejourney.com or you can learn more about our work by requesting a meeting below!

If you are currently a member, please reach out to your Member Services analyst for more information!

- CMS Innovation Center Models COVID-19 Related Adjustments; Oncology Care First Is a Big Step Toward Bundled Payments in Cancer Care, Authors Say; Fact sheet Oncology Care Model

- CMS Innovation Center Models COVID-19 Related Adjustments

- Fact sheet Oncology Care Model

- Feedback on the Direction, Challenges of the OCM; Three Benefits To The Oncology Care Model And Four Recommendations To Advance It

- COA Submits OCM 2.0 Proposal

- Three Benefits To The Oncology Care Model And Four Recommendations To Advance It

- Oncology Care First Model: Informal Request for Information; CMMI outlines potential next steps in oncology payment reform—the Oncology Care First Model

- Oncology Care First Model: Informal Request for Information

- Oncology Care First: What You Need to Know About the Proposed Oncology Care First Model