Appropriate Care: What’s the big deal?

It is well known that the United States spends more than any other nation on healthcare, but as a nation, our health outcomes miss the mark. As evidence-based medicine evolves, it is important that our healthcare practices adapt. With burnout at an all-time high and staff shortages on the rise, appropriate care helps health systems stay on track and care for their patient populations more effectively.

What is considered an “appropriate” definition?

Overall, appropriateness can be a complex concept for even the top quality improvement experts. The definition, considerations, and interpretations of appropriate care vary by nation. While there are a number of definitions of appropriateness, most definitions encompass the World Health Organization’s key requirements1 that care is:

- Effective (based on valid evidence)

- Efficient (cost-effectiveness)

- Consistent with the ethical principles and preferences of the relevant individual, community or society.

The RAND’s definition of appropriateness is the most widely used: “for an average group of patients presenting to an average US physician…the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the procedure is worth doing…excluding considerations of monetary cost”.2 Appropriateness requires input from various levels of healthcare experts and can have many clinical, economic, social, legal, and ethical considerations that must be evaluated. It is extremely important to consider who is making the judgment, the level of evidence that is being incorporated, and the process that is used in development to incorporate input.

From an economic perspective, appropriateness and the quality of care can be identified in three forms: overuse, underuse and misuse.3

- Overuse occurs when a service is provided even though its risk of harm exceeds its likely benefit, with the caveat of when it is clinically necessary. Economically, this also occurs when the cost of care exceeds the added benefit of care.

- Underuse is when a service is not provided even though it would be medically beneficial to the patient. Historically, this has been a pattern with Medicare enrollees.

- Misuse happens with medical errors that result in complications including things like an incorrect diagnosis, infections during a hospital stay, etc. Misuse can often result in harm to the patient that is preventable.

Overuse

Overuse of unnecessary care is most prominent in high-income nations. It is estimated that between 10-30% of all healthcare practices have little to no benefit to the patient.4 Among Medicare beneficiaries, 41% receive low-value care making up for 2.6% of overall annual spending.5 A recent study by Dr. Michael L. Barnett, Harvard School of Public Health, found that overuse was equally common for patients with Medicaid or patients that are uninsured compared to patients with private insurers.6

Today, only 32% of ACOs reported they have implemented strategies to reduce low-value care services.7 Studies have shown positive association between health systems without a teaching hospital and higher use of low value care.8 ACOs can take the learnings from these academic institutions’ success and incorporate their strategies into their own programs.

For decades, an annual mammogram was recommended for all women, regardless of breast cancer risk, from age 40 until death. The USPSTF, ACP, & ACS recommend against this blanket approach. While popular, these groups found that this practice was unneeded for this entire population. For example, for the elderly population who may have multiple comorbidities, a screening would not be beneficial. More importantly, an abundance of evidence showed screenings in inappropriate populations led to more patient harm than good. It is estimated that 85% of physicians follow this outdated practice. Is healthcare appropriate when the harm outweighs the benefit?

Underuse

Underuse occurs when a service is not provided (or accessible) to a patient even though it would be medically beneficial. Oftentimes, cost to a patient can be a barrier to appropriate use of care, and is an area that a physician wouldn’t always have control over in terms of adherence. A clinical trial found that enhancing prescription coverage increased compliance for medication adherence post myocardial infarction. In turn, this decreased rates of first major vascular events. This not only lowered patient spending but overall costs on the healthcare system.9

In addition to economic barriers, access to care can also lead to the underutilization of necessary medical intervention, particularly for rural populations. Studies have shown that population health in rural areas (as compared to urban) is inferior due to constraints around transportation, physician supply and retention, as well as scarcity of services offered.10 These obstacles perpetuate the underuse of basic and essential care, such as routine immunizations or cancer screenings.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the world. In the United States, approximately 151,030 diagnoses are made annually. Colorectal cancer can be fatal, unless it is caught early. Colon cancer screening rates have been slowly and steadily increasing over the past decade while incidence has decreased overall (apx. 1% per year). However, the incidence rate of early onset CRC (ages 40-50) is on the rise at 2% per year from 1995 to 2016. This rise has disproportionately affected black Americans.11

In 2018, the American Cancer Society was one of the first organizations to recognize the underuse of colon cancer screenings in this population and changed their guideline to screen patients at age 45 instead of 50.12 Many medical organizations soon followed this trend due to the abundance of scientific evidence. Lowering the screening age makes CRC screenings more accessible to patients, allows physicians to catch and treat cancer sooner, and improves health outcomes for a system.

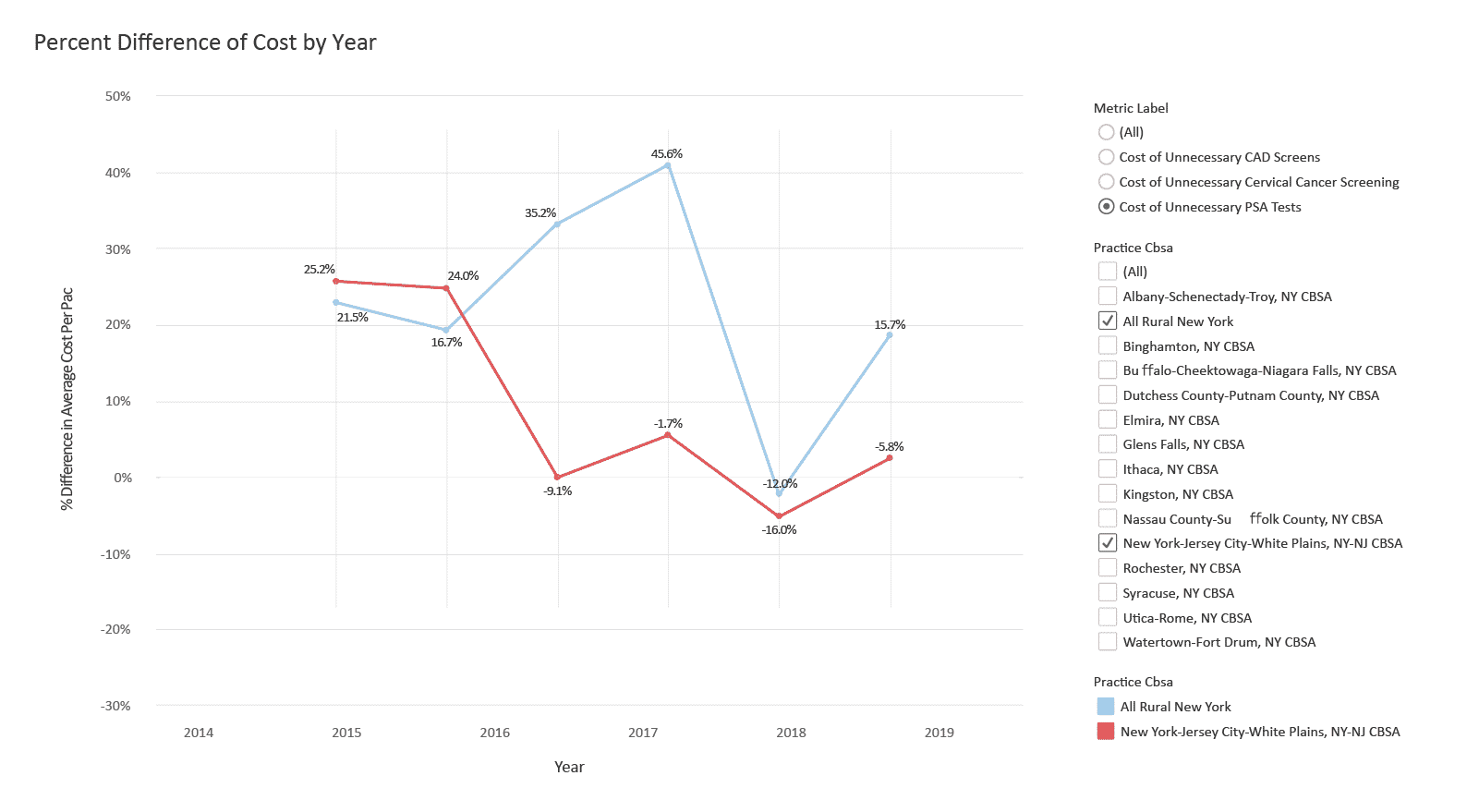

Compare Year-over-year Spend on Low-value Care

This dashboard compares year-over-year spend on low-value care across New York, a state selected for its stark rural vs. urban trends and high patient volume.

Misuse

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, burnout among healthcare professionals was a major crisis that had been evolving for years.13 In 2012, Shanafelt et al compared physician burnout to the general population, and the results were staggering: 37.9% for clinicians vs. 27.8% in the control group.14 The 2021 Medscape National Burnout and Suicide Report estimated the physician rate of burnout at about 43% overall, 51% for critical care, 50% rheumatology and 49% for infectious disease and nephrology.15 These numbers are staggering. This is important because often, these work environments can lead to costly mistakes in healthcare that directly impact at-risk patients seeking care within these environments. When our healthcare system is strained, steps can be missed in a patient’s care plan.

One in seven Medicare patients in a hospital experience a medical error.16 Approximately one in ten patients in high-income nations are harmed while being treated in a hospital, 50% of which are adverse events that are considered preventable.17 Misuse can be anything from misdiagnoses to preventable infections. Quality measures can help identify where and how often misuse occurs. However, educating clinicians on the dangers of misuse, while being sensitive to contributing factors, like burnout, can help foster productive conversations for improvement.

Inaccurate coding can hinder long term success for health systems and VBOs. Payments under value-based care are directly tied towards the risk of patient panels. Correctly coding HCCs bidirectionally accurately gives the financial support needed to better care for the appropriate patient panel. It also leads to better clinical interpretation of patient panels. This can be meaningful for education campaigns, flagging patients that are poorly controlled, or correctly identifying which patients have had their annual wellness visit.18 It is important to ensure that this type of coding is accurate.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation estimates that fraudulent billing accounts for 3-10% of all healthcare spending. Fraudulent billing leads to decreased quality of care and increased healthcare costs for the entire system. CMS breaks these into four categories: (1) mistakes resulting in administrative errors; (2) inefficiencies causing waste; (3) bending and abuse of rules; and (4) intentional, deceptive fraud. The Florida Department of Health published a case study in 2019 of a management company “pressuring and incentivizing” clinicians to meet certain production goals. This led to burnout, fraud and abuse, escalating costs, and billing when clinically unnecessary.19

Other Ways to Measure Appropriateness

There are many quality measures that evaluate the appropriateness of care or “high-value versus low-value care.” There are programs that are designed to improve high-value care within healthcare systems. Targeted quality “appropriateness” measures can help narrow in on eliminating low-value care. Many of these programs encompass tools for clinicians and open access educational resources to assist with the implementation of programs for health systems. Patient guides are equally as important. These tools empower patients to be their own advocate and take proactive evidenced-based steps to inform decisions with their care team.

High-Value Care Programs and Resources

| Name | Quality Measures | Incentive Payments | Specialist Input | Clinical Practice Guidelines and Recommendations | Education Modules/Curriculum | Implementation Resources for Clinicians | Patient Shared Decision Making Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American College of Physicians High Value Care Initiative | X | X | X | X | |||

| Choosing Wisely Program | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| CMS Value-based Care Programs | X | X | X | ||||

| Global Appropriateness Measures | X | X | |||||

| USPSTF “D” Recommendations | X | X | X | X |

CMS has developed a variety of value-based care programs targeted at improving high-value care. These include Alternative Payment Models (APMs), Merit Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, and more. One of the newest APMs, Accountable Care Organization Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (ACO REACH) Model promotes savings for entities and their preferred providers. In addition to the programs’ required quality measures, implementing appropriateness measures can help lower costs for the program and improve health outcomes for their beneficiaries. This can be used to increase savings and, as a result, the incentive payments to participating providers for more targeted quality care.

Using Data to Evaluate Appropriate Use of Healthcare Using Choosing Wisely Measures

Healthcare systems can have an impact on implementation and quality of care. We analyzed data from different communities within the state of New York, a region we selected for its drastic rural vs. urban populations and high patient volume, and observed variation by geographic region. For example, using Medicare FFS claims data, historically, we can see that healthcare providers near New York City have a much lower rate of unnecessary prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood tests to screen men for prostate cancer, a key measure identified under the Choosing Wisely, an initiative to help physicians and their patients make more informed medical decisions using evidence-based clinical information.20

These data show the presence of unnecessary PSA tests across different regions within New York state, and the percent change in spending towards PSA tests year-over-year. For example, in rural New York, unnecessary PSA spending incrementally increased in rural New York, particularly during 2015 through 2017, while PSA costs trended downward in urban areas like New York City, Newark, and Jersey City.

This not only impacts the healthcare system, but can create a financial burden to the patient. The average cost of a PSA test is $40. Additional fees can include up to $350 for consultation and up to $200 for professional fees. While Medicare Part B covers 100% of the test, if a male patient is over 50, 20% of additional costs are left with the patient.21 If a patient does not meet the criteria and is tested inappropriately, they can be stuck with a large bill. However, most often, a PSA test is not needed.

Up to 25% of men with a high PSA have prostate cancer. Most of these cancers do not cause harm to the patient. For example, in older men it is common to have slow-growing cancer cells on their prostate gland. Furthermore, a high PSA is more likely due to: an enlarged prostate gland, a prostate infection, recent sexual activity, a recent, long bike ride, (etc.).22 Testing patients when not clinically necessary is harmful and can cause avoidable distress, especially for patients near the end of life.

Putting Measures Into Practice

Data can be an incredibly valuable tool for identifying areas of opportunity with relevant measures. CareJourney helps hundreds of healthcare leaders use data to identify quality practice groups to expand health plan networks, highlight targeted saving opportunities for ACO REACH, and promote high-value care in health systems. When implementing a program to reduce low-value care, it is important to have a plan of action to gain buy-in from all stakeholders. Using these tips from University of Rochester School of Medicine with the CareJourney Provider Scorecard can be an effective way to manage appropriateness with clinicians.23

Quality Scorecard Overview

CareJourney’s Provider Performance Index (PPI) is a trusted, transparent method to quickly and comprehensively evaluate quality as well as cost. CareJourney has worked with stakeholders from our 100+ members across the healthcare industry to develop scores that are encompassing and actionable to evaluate provider performance. They are powered by three differentiated features:

- Robust, Longitudinal Data – built using the only fully joinable claims data source available for a comprehensive view of patient journeys, upon which to evaluate clinicians.

- Transparent Methodologies – The CareJourney PPI aggregates and evaluates quality and cost using open, granular methods.

- Trusted Enrichments – The PPI evaluates quality using industry-accepted assessments of low-value or avoidable care.

The PPI scores are risk-adjusted, benchmarked regionally, and based on CareJourney’s Taxonomy. The scores are derived from industry measures established by multiple quality health organizations. Our quality score encompasses quality from multiple perspectives, including appropriateness of care.

How CareJourney Can Help Get You Started

CareJourney’s platform has helped VBOs across the nation fuel quality improvement discussions with clinicians. We have worked with many DCEs on projections, health plans on building high-value care networks, and VBOs on strategies to reduce low-value care. If you are interested in exploring how CareJourney’s analytics can help your organization succeed, we want to hear from you.

Currently a member and want more information? Please reach out to your member services representative.

If you’re not a CareJourney member, email us at jumpstart@carejourney.com, or you can learn more by requesting a meeting.

Not ready for a meeting? Check out our resources to learn how CareJourney helps payer, provider, and pharma organizations reduce the total cost of care and improve care quality.

- https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/119936/E70446.pdf

- https://www.rand.org/news/press/2021/02/16.html

- https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/reports/07-17-healthcare_testimony.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6307334/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4241845/

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2617277

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2779118

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2784487

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1107913

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500097/

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/colorectal-cancer-epidemiology-risk-factors-and-protective-factors

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp200314

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22911330/

- https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456

- https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/patients-consumers/care-planning/errors/20tips/20tips.pdf

- https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/patient_safety/patient-safety-fact-file.pdf

- How to Succeed in Value Based Care. James Dom Dura. American Academy of Family Physicians.

- https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/what-should-health-care-organizations-do-reduce-billing-fraud-and-abuse/2020-03

- https://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/psa-test-for-prostate-cancer/

- https://www.helpadvisor.com/medicare/does-medicare-cover-a-prostate-specific-antigen-(psa)-test

- https://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/psa-test-for-prostate-cancer/