How do you Define Quality?

What is a “quality” physician? Depending on the stakeholder, there will likely be a different answer. A clinician’s response would vary depending on their specialty, training, and practice setting. At the same time, a patient would place greater value in bedside manner and shared decision making. A payer might tell you it is a clinician that eliminates the most waste.

Different types of quality measures were created to systematically evaluate health care providers in each aspect of patient care. When implementing a quality improvement program with your physicians, it is important to keep multiple perspectives in mind.

Physician scorecards can be a powerful tool to use as a starting point to bring together quality improvement specialists and clinicians. It can serve as the foundation to facilitate dynamic conversations with clinicians. While every scorecard has limitations, CareJourney’s goal is to combine these perspectives into a quality score that is actionable with our Provider Performance Index (PPI).

Quality Measures 101

What is a Quality Measure?

Quality measures are standards to evaluate performance against when caring for patients. Different measures account for different perspectives depending on the data source and sponsoring organization. They are used to not only benchmark individual clinicians and distribute bonus payments, but also to evaluate facilities, health systems, treatments, and care coordination.1

While each measure type is unique, there are six guiding principles that define a successful quality measure from The Institute of Medicine (IOM):2

- Safe: Methods that avoid harming patients.

- Effective: All patient care should be evidenced based, guard against over or under use.

- Patient-centered: Care centralizes individual patient preferences, needs, and incorporates patient’s values.

- Timely: Reduces delays that can be harmful.

- Efficient: Reducing all forms of waste, including equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy.

- Equitable: Providing care that is consistent in quality regardless of a patient’s gender, race, sexual orientation, religion, geographic location, or socioeconomic status.

How a Quality Measure is Born

Many private and public sector organizations develop quality measures. They are typically based on the latest clinical guidelines or technical reviews in an area. Guidelines rank all of the existing evidence in a condition or treatment and make recommendations based on the findings from the field. When a recommendation has strong enough evidence, a measure is created.

The National Quality Forum (NQF) evaluates measures in 15 different areas from private and public sector organizations. Each area has a multi-stakeholder consensus process where measures are vetted, evaluated, and scaled. NQF-endorsed measures inform the National Quality Strategy (NQS). NQS serves as the overarching framework to improve the quality of healthcare in the United States. The NQS has a triple aim of better care, affordable care, and healthy people and communities.

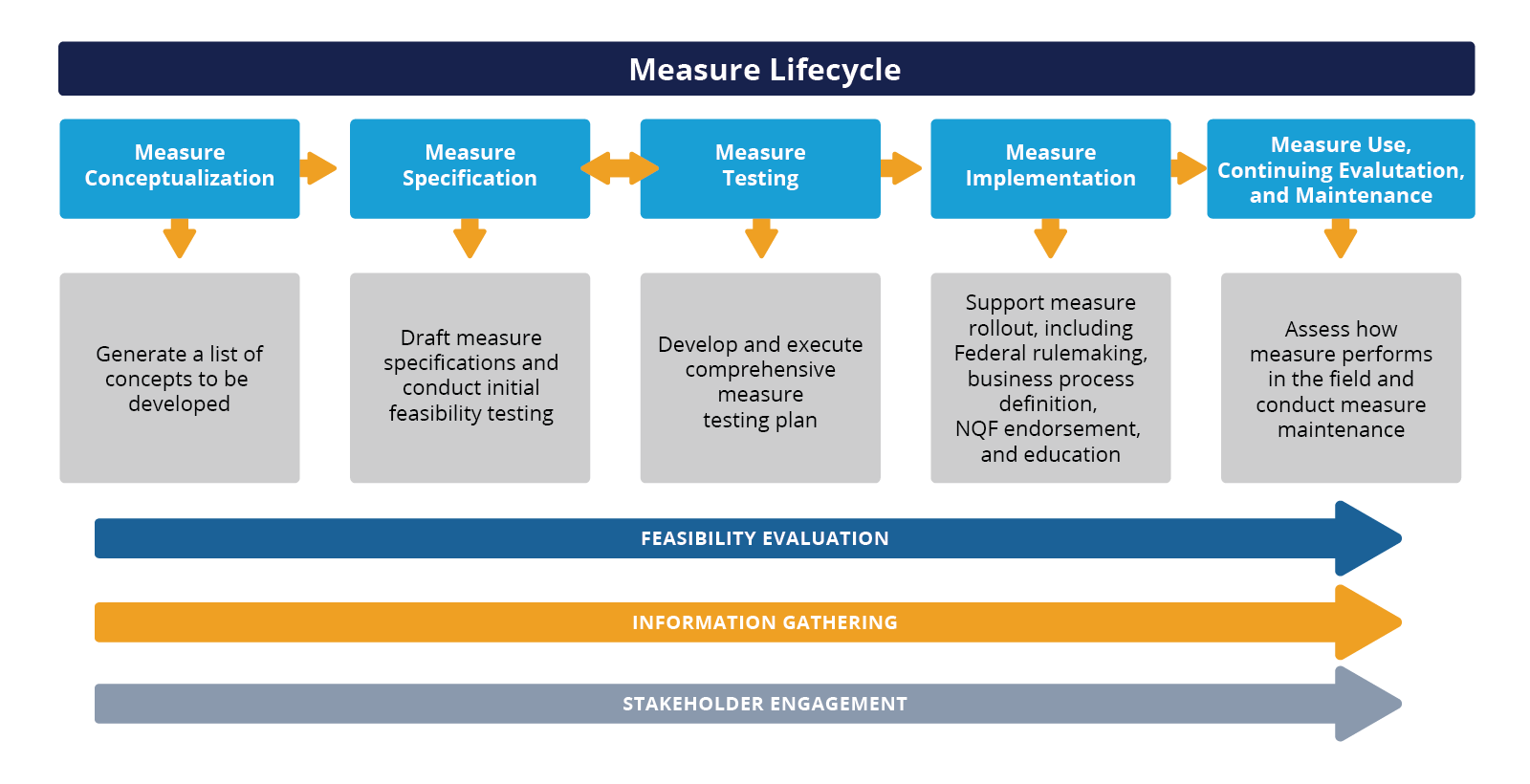

Measure Development Process

High-level view of major measure lifecycle tasks

Understanding how a measure is developed can arm you in evaluating measure performance. Creating accompanying educational materials based on the research that informed a specific measure can be an incredibly powerful tool. This helps present measures in a way that is clinically relevant.

Measures are continuously tested and updated. This is done to not only improve performance but also to improve the individual measures’ clinical rigor. When enough evidence emerges to a clinical standard practice, a measure can change or even retire completely.

What Happens When There are New Findings?

Many organizations rely on guidelines and literature reviews from the field to inform quality measure creation and modification. Because evidence-based medicine is constantly advancing, measures must be continuously evaluated and updated when research might contradict the original findings. There are instances where a new treatment might be discovered, new evidence for patient safety protocols comes to light, or the prevalence of a condition increases.

In mid-2021, you might have seen buzz around lowering the screening age for Colorectal Cancer to 45 in multiple organizations’ clinical guidance. In May of the same year, the US Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF) updated their recommendations to:

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Adults aged 50 to 75 years | The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer in all adults aged 50 to 75 years. | A |

| Adults aged 45 to 49 years | The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer in adults aged 45 to 49 years. | B |

| Adults aged 76 to 85 years | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians selectively offer screening for colorectal cancer in adults aged 76 to 85 years. Evidence indicates that the net benefit of screening all persons in this age group is small. In determining whether this service is appropriate in individual cases, patients and clinicians should consider the patient’s overall health, prior screening history, and preferences. | C |

Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH explains in her accompanying editorial, that “a concerning increase in colorectal cancer incidence among younger individuals (i.e., younger than 50 years; defined as young-onset colorectal cancer) has been documented since the mid-1990s, with 11% of colon cancers and 15% of rectal cancers in 2020 occurring among patients younger than 50 years, compared with 5% and 9%, respectively, in 2010”.4

While the shift to 45 has been endorsed by most specialty societies because of the new emerging evidence, most quality measures still reflect the previous 50 year recommendation. If research continues to support these findings and there is a confirmed benefit when these measures are refined and tested, we will likely see CRC screening measures begin to shift over the next few years.

Gone But Not Forgotten: Retired Quality Measures

Every year, organizations that develop quality measures will review them to determine whether there is a need to update or retire them. Reasons for retirement include situations where there is new evidence, enhancements to technology, no longer a need, or simply a more effective measure has been developed that better meets the needs of the field.

One of the most famous examples of this is NCQA’s percentage of patients with acute myocardial infarction who receive a prescription for beta-blockers within seven days of hospital discharge. This measure was developed in 1996 and was used for a decade. However, over time, the data showed that there was no longer a need for the measure. It was retired simply because there was little variation across health plans. As a whole, healthcare systems widely adopted this practice.5

How did this happen? Dr. Thomas Lee lays out all of the lessons learned from the success in his editorial. We will explore one component, Get With the Guidelines, more in depth later.

Learn How to Effectively Evaluate Quality Measures by Specialty

Access the data dashboard to evaluate state-level quality measure compliance for cardiologists, and use CareJourney’s taxonomy for more accurate benchmarking when evaluating a practice group’s performance.

Types of Quality Measures

Depending on the organization, the names and descriptions of quality measures will vary. Measure types can be renamed or categorized because of legislation, consensus, or a different methodology (depending on the organization). As such, the exact measure type and description can vary from CMS’s definition.

| Measure Type | CMS Definition3 | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Composite Measure | A composite measure is a measure that contains two or more individual measures, resulting in a single measure and a single score. | Pediatric Quality Indicators #19 (PDI #19) |

| Cost/Resource Use Measure | A cost/resource use measure is a measure of health services counts (in terms of units or dollars) applied to a population or event (including diagnoses, procedures, or encounters). A resource use measure counts the frequency of use of defined health system resources. Some may further apply a dollar amount (e.g., allowable charges, paid amounts, or standardized prices) to each unit of resource use. | Health Partners Total Cost Index |

| Efficiency Measure | An efficiency measure is the cost of care (inputs to the health system in the form of expenditures and other resources) associated with a specified level of health outcome. | Total OR Time |

| Intermediate Outcome Measure | An intermediate outcome measure is a measure that assesses the change produced by a healthcare intervention that leads to a long-term outcome. | HF-1 Discharge instructions |

| Outcome Measure | An outcome measure is a measure that focuses on the health status of a patient (or change in health status) resulting from healthcare—desirable or adverse. | PSI 04 – Death Rate among Surgical Inpatients with Serious Treatable Complications |

| Patient-Reported Outcome-Based Performance Measure (PRO-PM) | A patient-reported outcome-based performance measure (PRO-PM) is a performance measure that is based on patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) data aggregated for an accountable healthcare entity. The data are collected directly from the patient using the PROM tool, which can be an instrument, scale, or single-item measure. | PROMIS Item Bank v. 1.0 – Emotional Distress – Depression |

| Population Health Quality Measure | A population health quality measure is a broadly applicable indicator that reflects the quality of a group’s overall health and well-being. Topics include access to care, clinical outcomes, coordination of care and community services, health behaviors, preventive care and screening and utilization of health services. | NQF 0034 – Colorectal Cancer Screening |

| Process Measure | A process measure is a measure that focuses on steps that should be followed to provide good care. There should be a scientific basis for believing that the process, when executed well, will increase the probability of achieving a desired outcome. | Emergency department use without hospitalization |

| Structure Measure | A structure measure, also known as a structural measure, is a measure that assesses features of a healthcare organization or clinician relevant to its capacity to provide good healthcare. | NQF 0650: Melanoma: Continuity of Care |

It is important to understand the measure type when implementing quality measures into practice. Depending on the measure type, a physician will have a different method for improvement. For example, if a healthcare provider scores low in a process measure, an educational campaign that highlights the steps of a care pathway could be beneficial. Some of these can even be implemented into EHRs to make process improvement as seamless as possible.

Case Study: Using Quality Measures Effectively

Knowing the type of quality measure you are utilizing, the research that informed a measure, and area of improvement can be an incredibly powerful tool. Making quality measures easy to use and comprehend is a key component of implementation. Many successful programs have capitalized on this strategy.

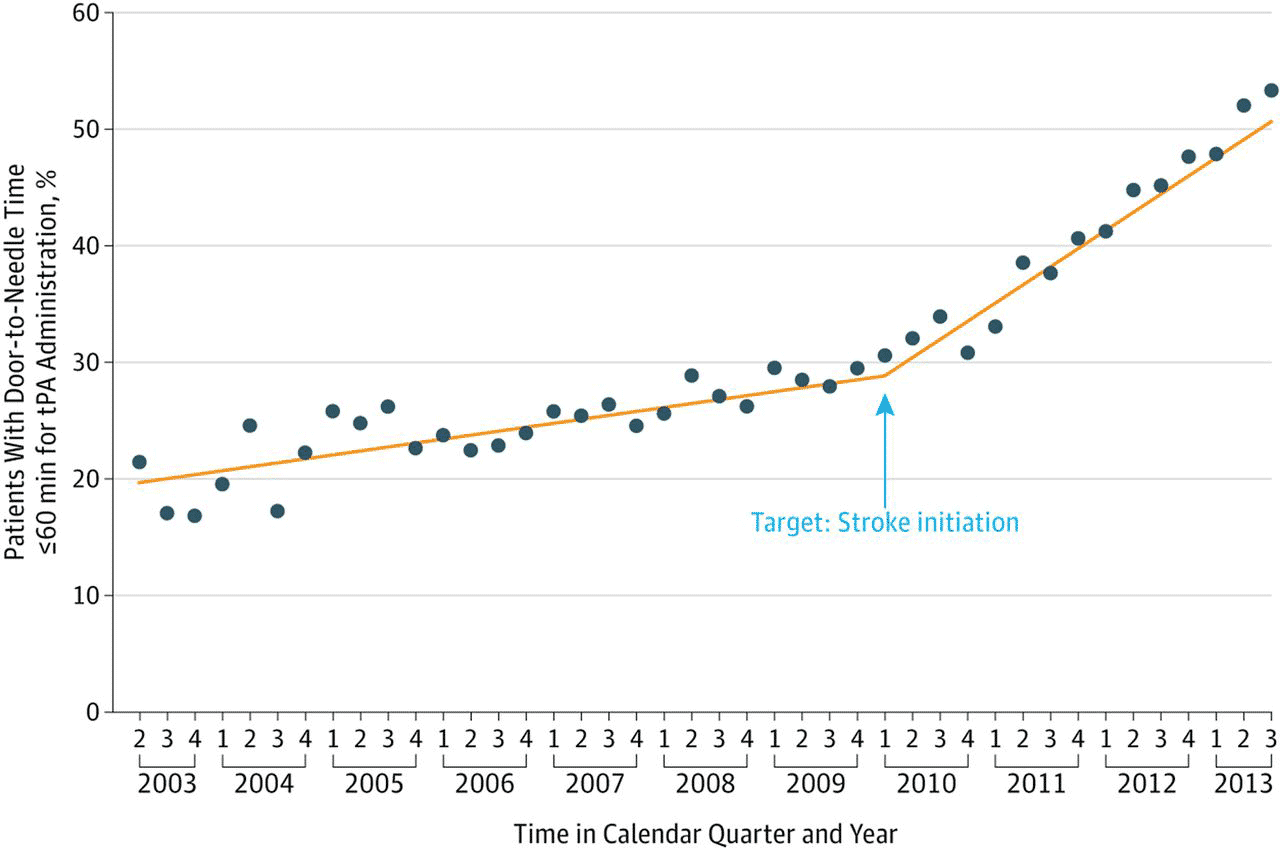

One of the large and well-known quality improvement programs is the American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines: Stroke (GWTG), with 2.5 million patients enrolled. The aim of the program was to shorten the time of treatment for patients with strokes. The GWTG program completely transformed stroke care starting with evolving practice with the EMS team through the discharge.

One major component, in addition to traditional measure registry reporting, was an accompanying resource center. This gave healthcare providers access to all relevant guidelines, patient guides, implementation tips, and an education series with workshops and webinars. The American Heart Association identified 10 best practices. Hospitals that participated were encouraged to add in their own 10 best practices. This allowed each hospital to tailor the program to their own improvement needs and incorporate the perspective of their team.6

The results spoke for themselves:

Impact of the Target: Stroke quality improvement initiative. Time trend in the proportion of patients with door-to-needle times for tPA ≤60 min during the preintervention and postintervention periods of Target: Stroke. Copyright ©2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

Measure compliance improved after six months of initiation to the program. As a result, the participating health systems’ performance increased across the board.

Admissions from roughly 1,500 hospitals over five years showed:7

- 4.3% increase in discharge antithrombotics

- 41.9% increase in IV tPA use in eligible patients

- 51.0% increase in smoking cessation education

- 20.8% increase in the composite score and 40.3% increase in the defect-free care measure

GWTG medicare beneficiaries had an overall increase in the proportion of patients that could be discharged. At the same time, mortality and length of stay for stroke patients trended downward for medicare beneficiaries. Dozens of subsequent studies from the registry findings informed more improvement measures. It became a nationally recognized blueprint for quality improvement for condition specific measure implementation.8

Where Can you Find Existing Quality Measures?

There are various organizations that produce quality measures. Different measures are utilized more frequently depending on the stakeholder. Various stakeholders might debate which measures are the most methodologically rigorous compared to others. However, it is important to remember each organization has the same mission that unites them: to improve patient care.

| Name | Source | Summary | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAHPS | AHRQ | CAHPS is a survey that is designed to measure patient experience. Patient experience is defined as “the range of interactions a patient has with the health system.” The surveys measure areas of quality through the patients’ lense, such as provider communication skills and ability to navigate the healthcare system easily.

While it is a PRO-PM measure in nature, it encompases composite measures to reflect a patient’s response in a rating score of 1 to 10. |

Survey |

| Choosing Wisely | ABIM/Misc. Speciality Societies | Choosing Wisely’s goal is to promote conversations between clinicians and patients to empower patients to seek care that is supported by evidence, not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received, free from harm, and is truly necessary. There is a library of patient resources to help facilitate these discussions.

For clinicians, there are selected measures by specialty, implementation plans, related literature, champions to help peers get started, and a learning center. The measure library is composed of the most “needed” areas of low-value care that is determined by representatives from various specialty societies. |

EHR |

| GAM | GAM | Global Appropriateness Measures were designed with specialty focus groups across various fields of medicine to find discernible patterns of unnecessary medical care in their specialty.

Using clinical wisdom from experts to create sophisticated algorithms which identify practice patterns that are excessive or inappropriate. |

Medicare and Commercial |

| HEDIS | NCQA | HEDIS measures are the most widely adopted measures by health plans for performance improvement. Health plans submit their data via IDSS files for NCQA accreditation. To incorporate patient experience, HEDIS also collects CAHPS survey data for HEDIS CAHPS accreditation.

HEDIS measures performance in effectiveness of care, access/availability of care, utilization, risk adjusted utilization, and misc. measures reported using electronic clinical data systems. The HEDIS User Group (HUG) provides members with resources on the process, new measures, and allows a forum to share best practices. |

Multiple |

| MIPS | QPP | The MIPS program was created to replace SGR. It is designed to reward clinicians that are designated as high-value and high-quality with payment increases. At the same time, clinicians that aren’t meeting the set performance standards payments are reduced.

MIPS were traditionally measured at the practice group (TIN) level. Clinicians now have the ability to combine multiple NPI/TINs into a single score. QPP participants include individuals, groups, virtual groups, and APM entities. |

Medicare |

| NQF Endorsed | Misc. Organizations | NQF developed a set of standards to evaluate quality measures. The standards are set by expert committees that include patient, provider, and payer voices. NQF endorsed measures can be found in their measure library. The library includes a variety of different measure types.

The Measure Application Partnership with CMS enables NQF to provide input to HHS on the selection of measures for public reporting and performance-based measurement payment programs. The MAP working group encompasses input from the Rural Health Advisory group and the Health Equity Advisory Group to improve decision making. |

Multiple |

| PQI | AHRQ | PQI measures were created to evaluate care in an outpatient setting. PQIs are a population-based indicator with the aim to target all cases of preventable complications in a population. They are used to measure appropriate care follow-up and avoidable readmission. PQIs are an integral piece of community health needs assessments. | Multiple |

| PSI | AHRQ | PSIs measure safety events that are avoidable to improve the delivery of healthcare. Their primary focus is to reduce in-hospital events and complications. These typically occur following surgeries, procedures, or childbirth. Hospitals use their benchmarks to highlight areas for potential improvement or further study into the incidence. | Multiple |

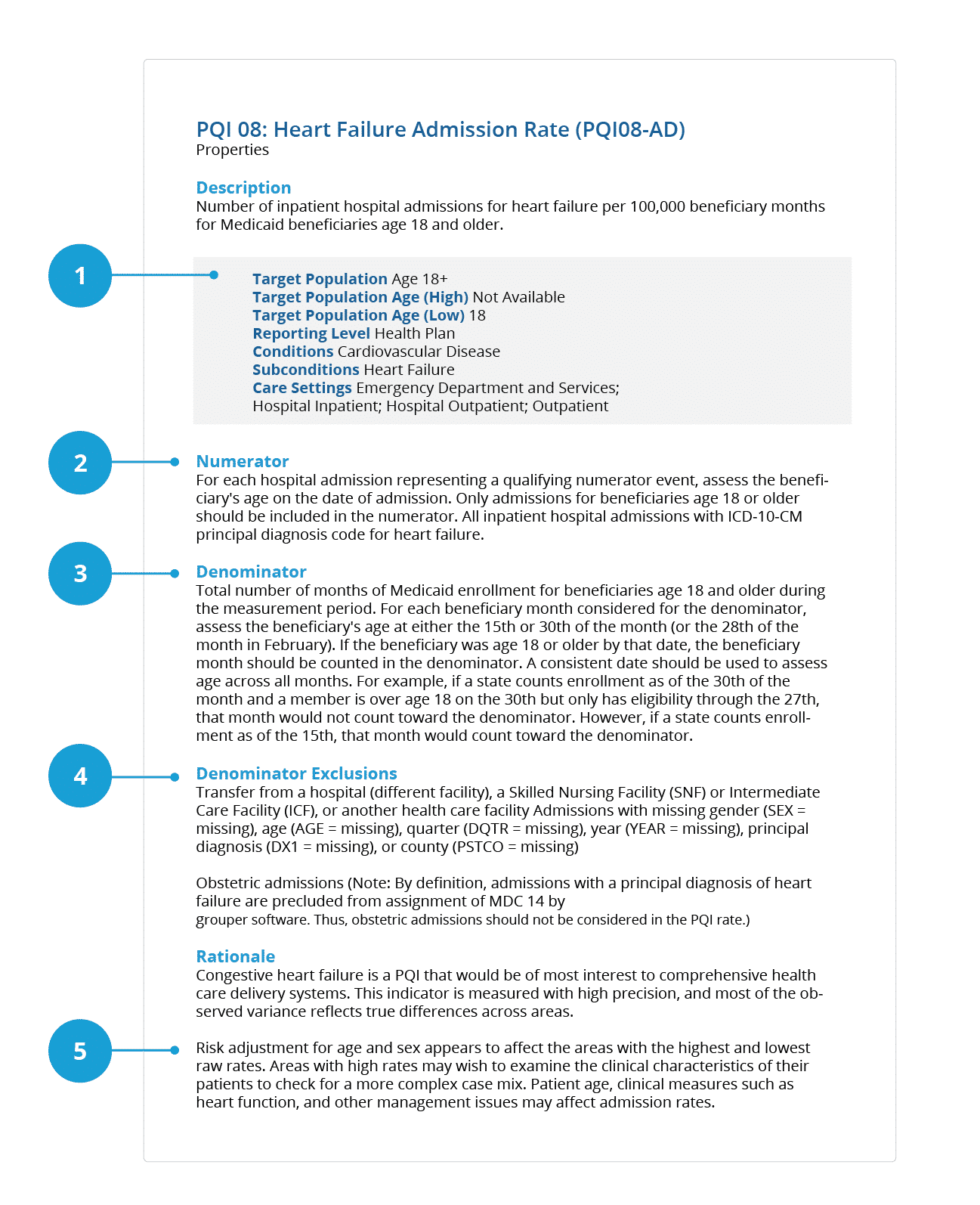

Breaking Down a Quality Measure

When working with quality measures, knowing how to interpret them is the first step in comprehending the results. There are three core parts to a quality measure: the target population, numerator, and denominator. From there, exclusions or exceptions may apply based on clinical necessity. These sections are defined by various codes that can be found in the individual measure publications.

1. Target/Initial Population: Refers to the cohort for selecting the denominator population. Some measures (e.g., ratioι measures) will require multiple target/initial populations, one for the numerator and one for the denominator.

2. Numerator: Describes the process, condition, event, or outcome that satisfies the measure focus or intent.

3. Denominator: Describes the population evaluated by the individual measure. The population defined by the denominator can be the same as the target/initial population or it can be a subset of the target/initial population to further constrain the population for the measure.

4. Denominator Exclusion: Denominator exclusions refer to criteria that result in removal of patients or cases from the denominator before calculating the numerator. An exclusion means that the numerator event is not applicable to those covered by the exclusion. Limit use to just those that are absolutely necessary.

5. Risk Adjustment/Stratification Scheme: Measure developers may define a stratification scheme in lieu of risk adjustment by stratifying the population based on their risk for an outcome of a procedure.

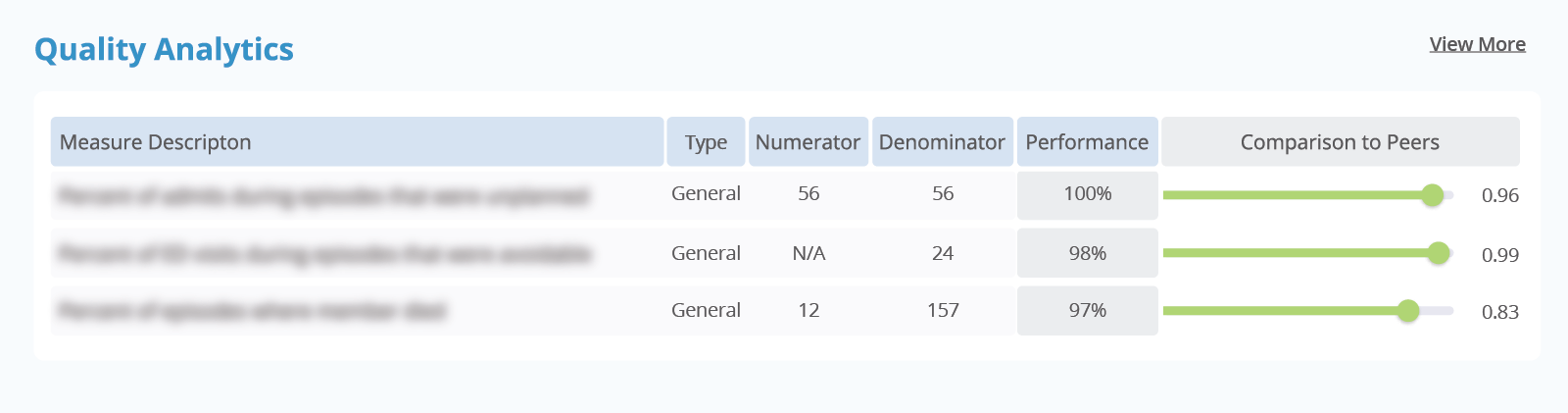

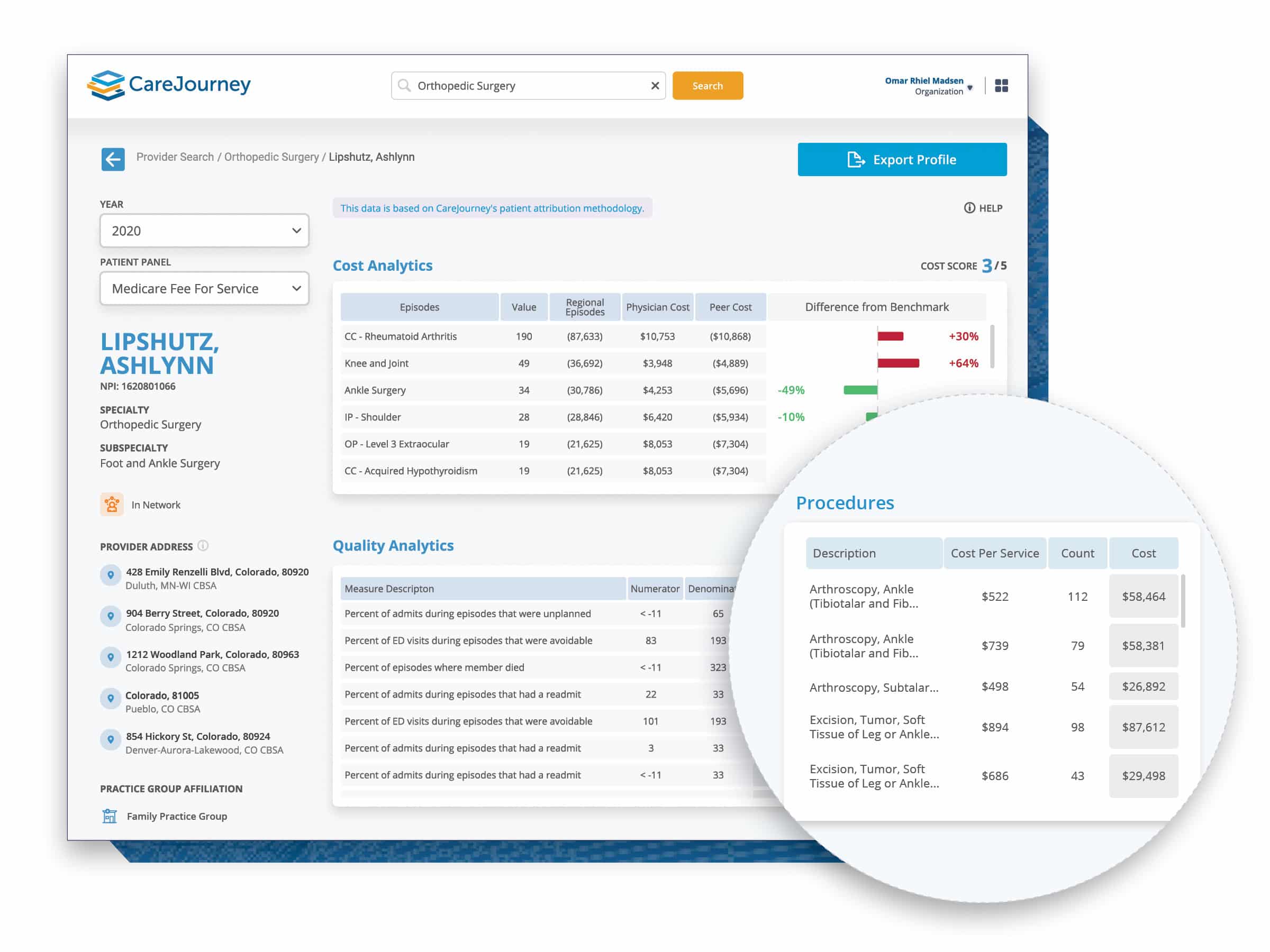

Knowing each section and the criteria for each measure can also help better interpret scorecards and facilitate more meaningful discussions with clinicians. For example, there is a numerator, denominator, and percentile for each score on CareJourney’s provider scorecard. CareJourney does the hard work of including the appropriate exclusion and exception criteria when calculating our scores.

Bringing it All Together: Measure Quality with the CareJourney Provider Performance Index

The CareJourney Provider Performance Index (PPI) and associated scorecard does all of the work for you in calculating individual measures, attributing them to the correct provider, and scoring providers based on their specialty, patient population, and geographic region.

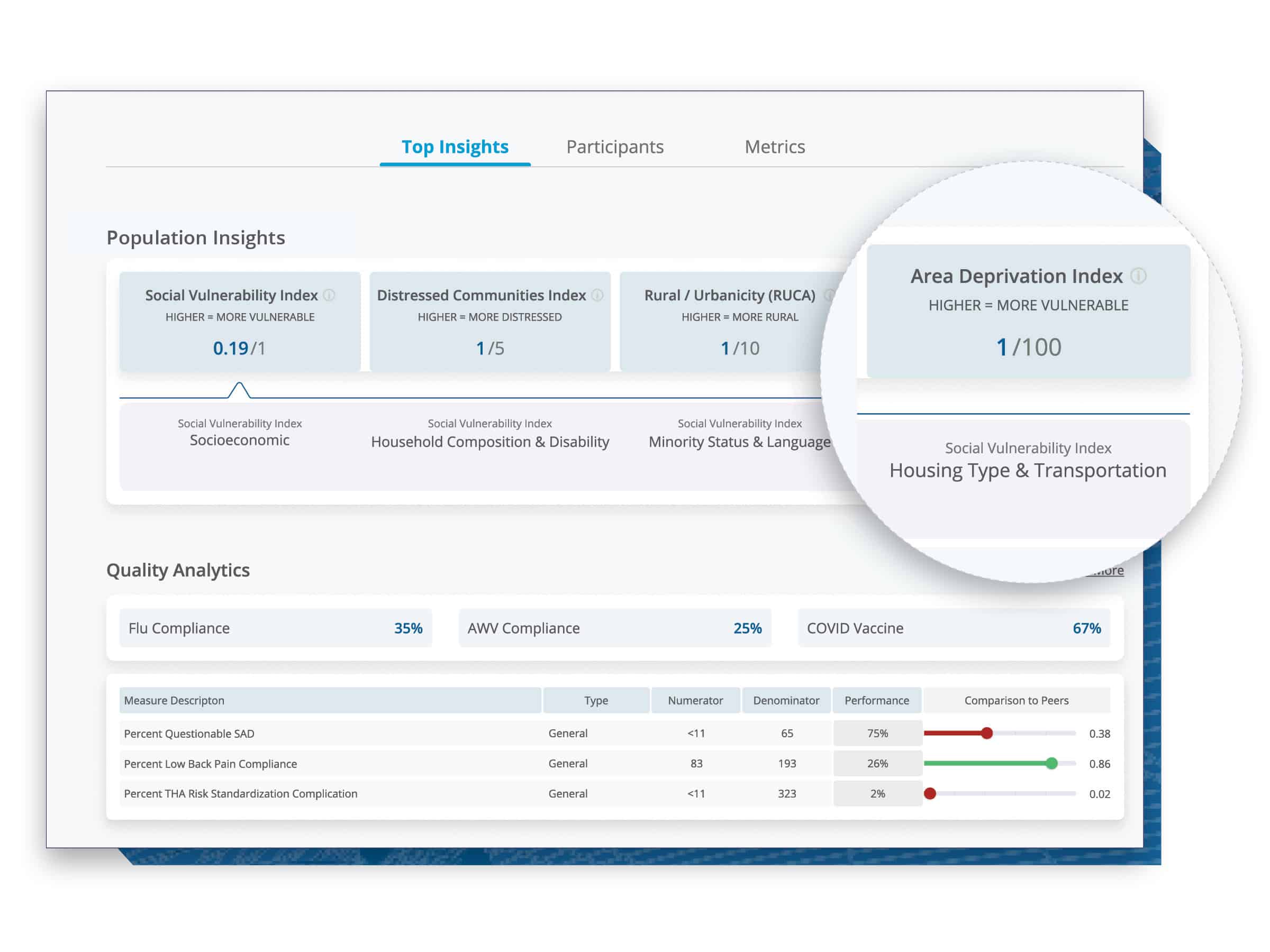

Our library comprises over 2 million physicians across the U.S., including PCPs and specialties, enabling you to holistically benchmark physicians against their peers and networks. With an open-sourced episode methodology commissioned by CMS, you can view and analyze physicians’ performance metrics that are distilled based on their actual practice patterns. With our provider taxonomy, you can accurately benchmark physicians with their “true peers.” Our tool reveals patient insights which enable you to understand the cohorts a physician is treating, including relevant episodes, procedures, and sites of service, to have a comprehensive view of the physician’s performance.

Quality Score Overview

CareJourney’s PPI is a trusted, transparent method to quickly and comprehensively evaluate quality as well as cost. CareJourney has worked with stakeholders from our 100+ members across the healthcare industry to develop scores that are encompassing and actionable to evaluate provider performance. They are powered by three differentiated features:

- Robust, longitudinal data – The PPI is built using the only fully joinable claims data source available for a comprehensive view of patient journeys, upon which to evaluate clinicians.

- Transparent methodologies – The PPI aggregates and evaluates quality and cost using open, granular methods.

- Trusted enrichments – The PPI evaluates quality using industry-accepted assessments of low value or avoidable care.

The PPI scores are risk adjusted, benchmarked regionally, and based on CareJourney’s Taxonomy. The scores are derived from industry measures established by multiple quality health organizations.

Tips for Success When Using the PPI Quality Scorecard for Quality Improvement

- Look at the breakdown of an overall score. A physician could have a high overall score, but still have areas of opportunity to streamline care.

- Come prepared. All materials should be easy to read, actionable, and centered around improving outcomes. Having the complete provider scorecard ready to share with your clinicians can work as the foundational starting point. It might also be helpful to read and bring relevant literature, such as related guidelines, quality brochures, and quick guides to reference.

- Consider the patient population your provider group is caring for. Knowing the HCC, patient demographics, and average income can paint a more accurate picture of a physician’s care setting. There might be other social determinants of health to consider when you are collaborating on strategies for improvement. Including CareJourney’s market profile in your resources can help stakeholders better understand that patient population.

- Keep an open mind. Remember the physician’s perspective. Not all clinicians are quality specialists. Not all performance managers are clinical experts. It is important to learn from each other to improve performance. While the data can give us a preview into performance, there is likely a much larger story behind each score.

Find a Middle Ground with Physicians by Centering the Patient

There is one thing that brings together almost every stakeholder in healthcare: the patient. A method that many of our members have used to improve physician performance is centering the patient. In a recent CareJourney webinar, Advanced Approaches to Determining Provider Performance, a member spoke on the importance of patient-centered care at their organization, and how their organization used this to improve health outcomes and appropriateness of care. While this might not be feasible in every setting, it can be a powerful tool to utilize when presenting scorecards to physicians.

How CareJourney Can Help Get You Started

The CareJourney platform has helped VBOs across the nation fuel quality improvement discussions with clinicians using our PPI Scorecard. If you are interested in exploring how CareJourney’s analytics can help your organization succeed, we want to hear from you.

Currently a member and want more information? Please reach out to your member services representative.

If you’re not a CareJourney member, email us at jumpstart@carejourney.com, or learn more by requesting a meeting.

Not ready for a meeting? Check out our resources to learn how CareJourney helps payer, provider, and pharma organizations reduce the total cost of care and improve care quality.

References

- ABCs of Measurement. National Quality Forum. https://www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/ABCs_of_Measurement.aspx

- Six domains of Healthcare Quality. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/six-domains.html

- CMS Measure Management Blueprint. CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/Blueprint.pdf

- Ng K, May FP, Schrag D. US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations for Colorectal Cancer Screening: Forty-Five Is the New Fifty. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1943–1945. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4133

- Lee T. Eulogy for a Quality Measure. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1175-1177 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp078102

- Get With the Guidelines: Stroke. The American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/get-with-the-guidelines/get-with-the-guidelines-stroke

- Ormseth CH, Sheth KN, Saver JL, et alThe American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines (GWTG)-Stroke development and impact on stroke careStroke and Vascular Neurology 2017;2:doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000092

- Ormseth CH, Sheth KN, Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH. The American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines (GWTG)-Stroke development and impact on stroke care. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2(2):94-105. Published 2017 May 29. doi:10.1136/svn-2017-000092