Background

Before the onset of COVID-19, many Medicare home health beneficiaries were already older and suffered from more chronic conditions (often multiple at the same time) than the average Medicare patient. In the wake of the pandemic and hospitals encouraging patients to remain at or return home to preserve capacity, many believe that not only will the profile of these Medicare patients become more acute, but that the model of home health care will endure and possibly even expand.

As a result of the pandemic, players throughout the healthcare industry – providers, payers, and patients – have been forced to take a hard look at how care was once utilized, how much it cost, who needed it, and whether it was truly necessary. In order for stakeholders to make claims about how the pandemic truly affected Medicare home health beneficiaries, it is imperative to look back and examine trends of where care was delivered and who utilized home health services before the virus spread. Essentially, understanding the profile of these home health patients pre-2020 will allow us to set the stage to test the effects of the pandemic’s impact once the dust settles.

Overview of Home Health

What does home health care include?

With improvements in medical sciences and technology, many treatments that could once only be done in a hospital can now be performanced in a patient’s home. Not only is home health usually less expensive, but it is often just as effective as caring for a patient in a hospital or skilled nursing facility. Short-term home health care focuses on treating an illness or injury, with the ultimate goal of helping patients regain their independence and become as self-sufficient as possible. On the other hand, long-term home health care is best suited for chronically ill or disabled patients and aims to help those individuals learn to live with their conditions.1

Home health care includes physical and occupational therapy, speech/language therapy, and medical social services. These services are provided by a variety of skilled health care professionals in the comfort of a patient’s home in order to coordinate the care and/or therapy recommended by a patient’s doctor. Home health staff teach the patient and/or any caretakers how to continue caring for the patient, which may include administering medication, wound care, therapy, and stress management. This education is particularly important for patients and their informal caregivers because most home health care is intermittent and part-time, meaning that there are limitations on the number of hours per day and days per week that patients can get skilled nursing or home health aide services.1,2

What does home health care not include?

Medicare home health care often gets confused with home-based primary care (HBPC), or the modern-day “house call.” Home health is often provided after a patient is hospitalized (e.g. following surgery) by nurses and physical, occupational, and speech therapists. To qualify, patients must have a Medicare-skilled need and a licensed provider. Despite the differences between short- and long-term home health, care does not typically last longer than two months.3

Meanwhile, HBPC is longitudinal and provides care for as long as a patient needs it, especially since many of these patients are the most medically complex (and therefore more costly to the health care system), in addition to being homebound and lacking continuous follow-up care. While HBPC patients may temporarily have some home health incorporated into their care for additional nursing and therapy services, they eventually stabilize and no longer require the skilled services associated with home health care. HBPC also provides significant palliative care services and commonly partners with palliative and hospice providers.3

Additionally, Medicare home health is not considered a long-term services and support (LTSS) program and does not provide unlimited 24/7 coverage. It also excludes custodial or personal care (if that is the only home care needed), household services (e.g. shopping, cleaning, and laundry when not related to a patient’s care plan), and meal deliveries. Home health care is limited to providing skilled care (instead of supporting activities of daily living, which is covered by Medicaid) and includes fewer than eight hours per day and less than 28 hours per week.3,4

How is home health care funded?

Patients have the option to select the home health agency that provides them with care, but their choices can be limited by agency availability or Medicare requirements. Some hospitals have their own home health agency (HHA) for patients to choose. However, if a patient is in a Medicare health plan, he or she may have to select an agency that is certified by Medicare, as Medicare will only pay for home health services provided by a home health agency that meets its standards.1

Additionally, patients must meet all of the following conditions in order to be eligible for Medicare-covered home health care:

- The patient’s provider determines that the patient requires medical care at home.

- The patient needs at least one of the following: intermittent (less than eight hours a day) skilled nursing care or physical, speech/language, and/or continued occupational therapy.

- The patient must be homebound or unable to leave his or her home without assistance.

- The home health agency must be a Medicare-certified program.1

If the above conditions are met, Medicare will cover the cost of the following on a part-time or intermittent basis:

- Skilled nursing care, which includes services and care that can only be performed by a registered nurse or a licensed practical nurse.

- Home health aide services, which can be completed by a professional that does not have a nursing license and include help with personal care, like bathing, using the toilet, or dressing. These services are not covered by Medicare unless the patient is also receiving skilled care.

- Physical, speech/language, and occupational therapy for as long as recommended by the patient’s doctor.

- Medical social services, such as counseling or help with finding resources in the community, to assist patients with social and emotional concerns related to their illness.

- Some medical supplies, like wound dressings. This does not include prescription drugs or biologicals.

- Medical equipment, like a wheelchair or walker.1

On the other hand, Medicare will not pay for:

- 24-hours-a-day care at home;

- Prescription drugs;

- Meal deliveries;

- Homemaker services, like shopping, cleaning, and laundry;

- Personal care provided by home health aides (like bathing, using the toilet, or help with getting dressed) when this is the only assistance that a patient needs.1

In 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented a new prospective payment system with a Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) that shifts reimbursement toward bundled payments based on patients’ clinical characteristics instead of fee-for-service payments based on the volume of therapy visits. As a result, home health providers receive two separate payments when care is initiated and when the episode of care is complete within 30 days. The motivation to change how CMS paid for home health services was rooted in an attempt to reduce costs while improving outcomes.2

Additionally, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was also passed in March 2020 as a $3 trillion stimulus package. In particular, the plan allocated $100 billion to health care providers, $40 billion of which was distributed to hospitals LTSS providers, including home health agencies that bill Medicare.2

For patients with low incomes and limited resources, some state programs like Medicaid may offer support for basic home health care and medical equipment. That being said, Medicaid coverage does differ from state to state.1

Request a meeting to see your chronic condition counts, HCC scores, BPCI episode costs, and utilization metrics!

Use of Home Health

The following trends were identified based on an analysis of Medicare fee-for-service data from 2018 and 2019.

Frailty Cohort

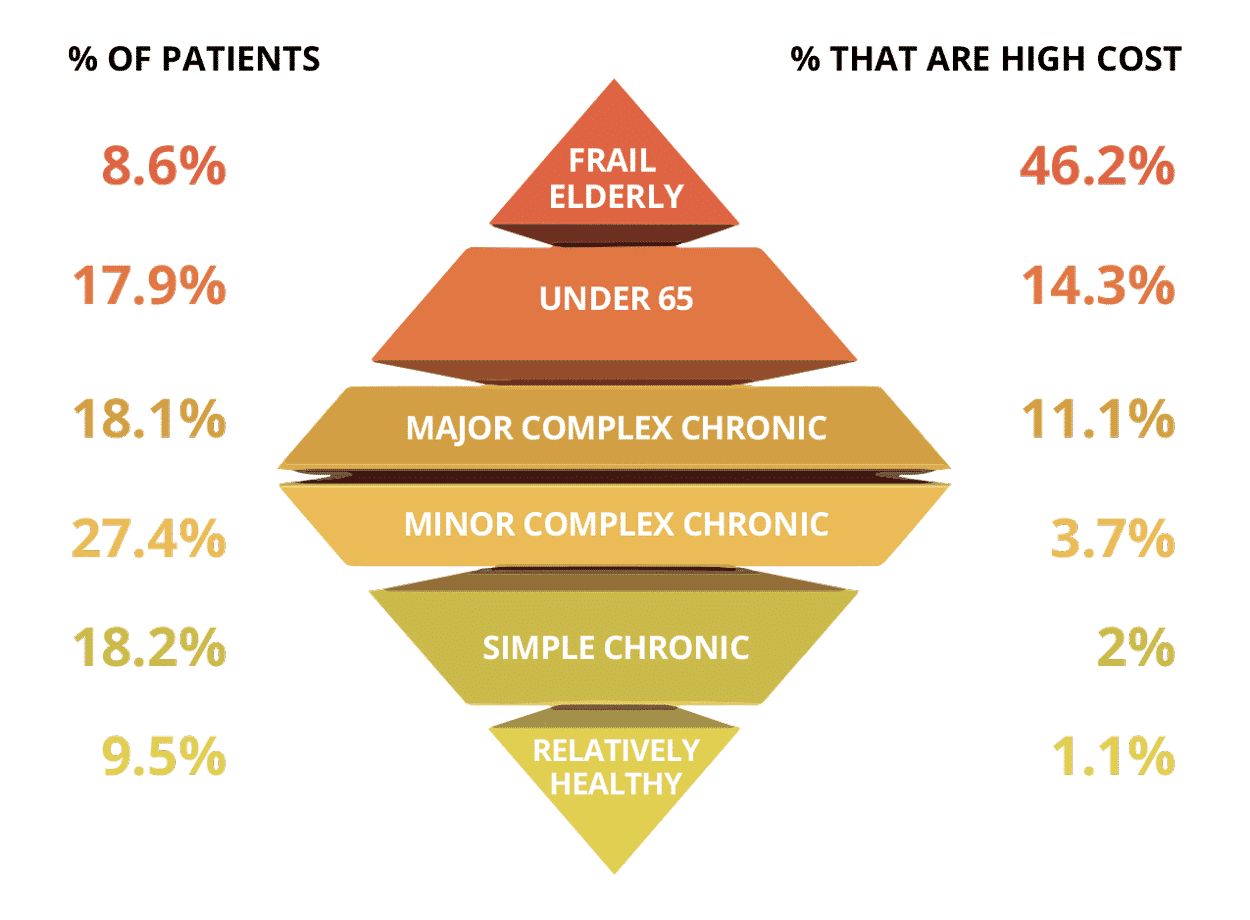

In a 2016 Harvard study, researchers segmented the Medicare population into patient cohorts as a strategy to identify which patients contributed to health care spending and develop meaningful interventions to control costs for those subgroups. Beneficiaries were categorized into six subgroups based on their Medicare fee-for-service claims, demographics, and comorbidities: under-65 disabled/end-stage renal disease (ESRD), frail elderly, major complex chronic, minor complex chronic, simple chronic, and relatively healthy. Following the study, researchers concluded that frail patients were the most likely to be high-cost (or in the highest 10% of spending), followed by the under-65 and major complex chronic groups, as pictured below.5

Frailty Segmentation

Applying the Harvard Patient Segmentation Model to home health care beneficiaries in 2018 and 2019, the frail elderly subset of Medicare patients unsurprisingly accounted for both the highest number of home health admissions and the greatest total average of home health care spend per member per month (PMPM) across the country.

Location

From 2018-2019, it was expected that total home health admissions were higher in more populous states (Texas, California, Florida, Illinois, and New York) and counties. However, differences in admissions and PMPM became more apparent at the county level. For example, in Texas, the greatest number of HHA admits for the Medicare population occurred in counties that overlapped with large metropolitan areas (e.g. Harris County / Houston and Dallas County / Dallas), but counties with the highest average PMPM in Texas (e.g. Duval, Jim Wells, and Jim Hogg) were actually located in rural communities. This is based on an analysis done on CareJourney’s access to over 60M lives of Medicare FFS data.

According to a 2014 study on differences in case mix between rural and urban recipients of home health care, rural home health patients are more likely than their urban counterparts to: be severely ill or in fragile condition; have more risk factors for hospitalization; need respiratory treatments and therapies; and have surgical wounds requiring treatment. Home health care allows these patients to delay hospitalization (which may be challenging to access anyways) and remain in their homes as long as possible.6 On top of that, these five counties in Texas were also deemed Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) due to the lack of primary care providers practicing in these regions, indicating a scarcity of health care resources in the region that could have contributed to the increased need to obtain home health.7

For home health agencies and hospital systems that both care for Medicare patients in these regions, understanding what factors make these communities so vulnerable could help providers understand how that plays into the high-acuity profile of these beneficiaries, identify opportunities to reduce the need for hospitalization in the first place, and ultimately curb home health expenses in the future.

Age

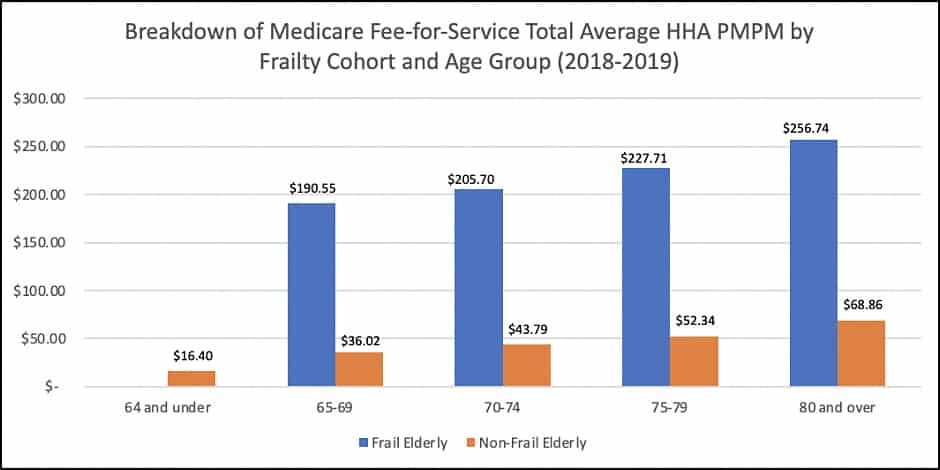

The greatest number of home health admissions and spend between 2018 and 2019 was associated with Medicare beneficiaries that were ages 80 and over. These patients experienced more complex conditions and were perhaps limited in their ability to access and obtain care on a more regular basis due to their age. Interestingly, even though frail elderly patients only make up about 8-9% of the population, they accounted for 49.5% of all HHA admissions between 2018-2019, as seen in Table 1.

In the graph below, the “Non-Frail Elderly” category includes the following Patient Segmentation subgroups: under-65 disabled/end-stage renal disease (ESRD), major complex chronic, minor complex chronic, simple chronic, and relatively healthy. Again, average PMPM for frail elderly beneficiaries continued to exceed that for non-frail elderly patients.

Figure 1

*Note: Unweighted averages were used in this analysis.

Gender

In 2018 and 2019, female Medicare beneficiaries were the highest users of home health care services and accounted for the greatest average home health PMPM. A breakdown of HHA admissions and PMPM can be found in Tables 1-2 below.

Race

While Non-Hispanic White Medicare beneficiaries had the highest number of home health care admissions, African American Medicare beneficiaries accounted for the greatest average home health PMPM in 2018 and 2019.

The following tables further illustrate home health admissions and average PMPM broken down by frailty cohorts. By understanding which Medicare beneficiaries are utilizing home health services the most and what it typically costs to care for them, providers and health systems can identify opportunities to better advocate for those patients.

Table 1: HHA Admissions by Frailty Cohort (2018-2019)**

| Frail Elderly | Non-Frail Elderly | All Medicare | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Admits | 5,841,895 (49.5%) | 5,969,040 (50.5%) | 11,810,935 |

| Avg. HCC | 1.68 | 0.86 | 0.96 |

| Age | |||

| 64 & Under | – | 1,401,194 (11.9%) | 1,401,194 (11.9%) |

| 65-69 | 547,332 (4.6%) | 686,726 (5.8%) | 1,234,058 (10.4%) |

| 70-74 | 792,096 (6.7%) | 839,618 (7.1%) | 1,631,714 (13.8%) |

| 75-79 | 957,706 (8.1%) | 838,503 (7.1%) | 1,796,209 (15.2%) |

| 80 & Over | 3,544,761 (30.0%) | 2,202,999 (18.7%) | 5,747,760 (48.7%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 2,076,615 (17.6%) | 2,474,105 (20.9%) | 4,550,720 (38.5%) |

| Female | 3,765,280 (31.9%) | 3,494,935 (29.6%) | 7,260,215 (61.5%) |

| Race | |||

| African American | 529,788 (4.5%) | 899,391 (7.6%) | 1,429,179 (12.1%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 4,988,583 (42.2%) | 4,607,098 (39.0%) | 9,595,681 (81.2%) |

| Other | 323,524 (2.7%) | 462,551 (3.9%) | 786,075 (6.7%) |

**Note: All percentages are listed with total Medicare admits as the denominator.

Table 2: HHA Average PMPM by Frailty Cohort (2018-2019)

| Frail Elderly | Non-Frail Elderly | All Medicare | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. HCC | 1.68 | 0.86 | 0.96 |

| Age | |||

| 64 & Under | – | $16.40 | $27.90 |

| 65-69 | $190.55 | $36.02 | $18.99 |

| 70-74 | $205.70 | $43.79 | $25.77 |

| 75-79 | $227.71 | $52.34 | $41.62 |

| 80 & Over | $256.74 | $68.86 | $82.74 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | $220.34 | $18.09 | $33.54 |

| Female | $226.80 | $23.26 | $42.61 |

| Race | |||

| African American | $271.08 | $33.44 | $57.39 |

| Non-Hispanic White | $211.60 | $18.21 | $34.51 |

| Other | $248.47 | $17.56 | $28.39 |

Combined Factors

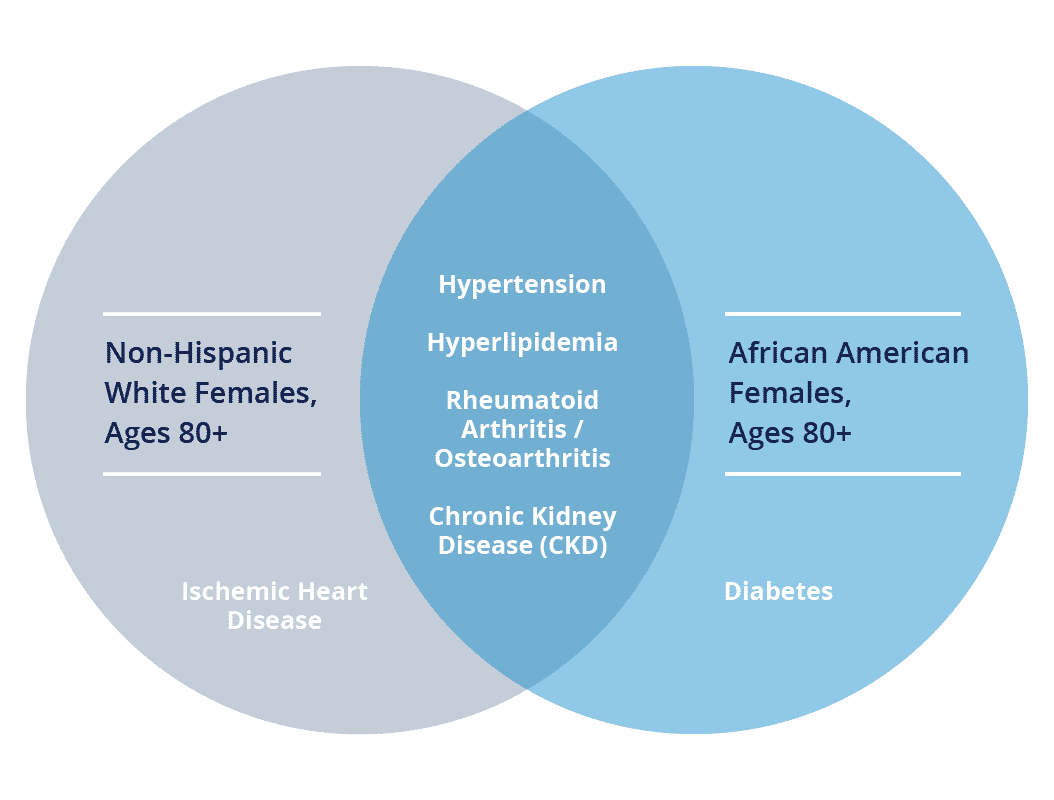

When measured for age, gender, and race, Non-Hispanic White females, ages 80 and over, had the most home health agency admissions (27% of total HHA admissions for all Medicare population). Meanwhile, African American females, ages 80 and over, comprised the greatest home health average PMPM in 2018 and 2019.

While a specific breakdown of the conditions these home health beneficiaries were treated for cannot be disclosed, the following conditions were most prevalent amongst both populations, respectively:

Chronic Condition Prevalence by Race, Age, and Gender Groups (2018-2019)

Innovation within Home-based Care

Home health is well positioned to offer care to beneficiaries in the comfort of their own homes, an idea that has become increasingly relevant during the onset of the global pandemic. Due to their older age and prevalence of chronic conditions, Medicare home health beneficiaries may be amongst those who were most impacted by COVID-19. On top of that, these patients have been less likely to undergo elective surgeries or allow providers into their homes out of fear of infection, suggesting that the pandemic may have resulted in a significant reduction in the use of home health care services.2

Before the pandemic, hospitals and doctors’ offices were often considered the traditional settings in which to deliver health care to Medicare beneficiaries (and all patients, for that matter). With increasing attention on alternative methods of providing care (including policy changes and recent trends in telehealth adoption), the industry may not have to look too far for ideas on how to be innovative. Some examples of historical initiatives in the home are described below.

Independence at Home Medicare Demonstration Program

In 2012, the Independence at Home (IAH) Demonstration was developed by the CMS Innovation Center to assess the ability of a home-based primary care model to improve care and the need for hospitalization, reduce Medicare spending, assist complex patients (i.e. those with multiple chronic conditions and functional limitations) on a regular basis, and improve patient and caregiver satisfaction.3,8

A list of participating sites that are involved in the IAH Demonstration can be found here. The program is entirely funded through cost savings generated by the house call practices that are a component of the initiative. CMS tracks the experience of beneficiaries through quality measures, and practices that successfully meet these measures while generating savings have the opportunity to receive incentive payments after satisfying a minimum savings requirement.8

In the first four years, IAH achieved millions of dollars in savings, including $32.9 million (an average reduction of $2,819 per beneficiary) in its fourth year. The program cited fewer 30-day readmissions, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits for beneficiaries, along with an overall increase in the quality of care, as evidenced by follow up communications within 48 hours of hospitalization, medication reconciliation, and documentation of advanced care preferences.3

Hospital at Home

In 2002, Hospital at HomeⓇ (HAH) was developed by researchers at Johns Hopkins University Schools of Medicine and Public Health and successfully tested in a National Demonstration and Evaluation Study to treat elderly patients who either did not want to go to the hospital or were at such risk of hospital-acquired infections and other adverse events that physicians kept them at home out of concern for their safety.6 The program was implemented at numerous sites around the United States by Veterans Affairs hospitals, health systems, home care providers, and managed care programs with the goal of treating acutely ill older adults, while improving patient safety, quality, and satisfaction.10

Early trials of the program yielded the following results:9,10

- Cost savings of approximately 30% compared to traditional inpatient care;

- Better clinical outcomes;

- Lower average length of stay;

- Fewer lab and diagnostic tests compared with similar patients in hospital acute care;

- Helped older adults to avoid common iatrogenic complications associated with stays in traditional acute care hospitals (e.g. delirium, polypharmacy, and functional decline);

- Advanced the Triple Aim (clinical quality, affordability, and exceptional patient experience).

In 2014, Mount Sinai Medical Center (New York, NY) was awarded a grant by CMS and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to develop HAH in a fee-for-service Medicare setting and to begin compiling data that would inform a possible 30-day bundled payment model for HAH care. The program is currently offered to patients who need to be admitted to the hospital for certain diseases, like community-acquired pneumonia, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cellulitis. If patients meet specific eligibility criteria, they can receive hospital-level care (including diagnostic tests and treatment therapies from doctors and nurses) in their own homes.10,11

Looking Ahead

By understanding the characteristics of Medicare home health patients and establishing a baseline of how they utilize this care, we can set the stage to analyze how COVID-19 may have impacted home health care delivery in the future. How can the industry learn from the outcomes of home health initiatives and other programs as we rethink care delivery after the pandemic? Based on what we know about how home health care was provided to Medicare beneficiaries and who needed that care the most before COVID-19, what steps can we take to ensure that these high-acuity patients don’t fall through the cracks in the future? By knowing what is and is not included in home health care, where are the opportunities to expand that definition in ways that take the most vulnerable communities into consideration?

Explore with CareJourney

With access to the complete CMS fee-for-service dataset, CareJourney can provide other valuable insights around HHA, as well as other post-acute settings of care (e.g. Skilled Nursing Facilities), that may include:

- Chronic condition counts;

- Hierarchical condition category (HCC) scores;

- Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) episode costs by HHA; and

- Cost and utilization metrics for the facilities and providers that treat Medicare home health beneficiaries.

Data for this analysis is a standard component of CareJourney’s platform, which enables users to dig into a geographic region and better understand subsets of the Medicare fee-for-service population in that market. Moreover, CareJourney’s tool allows users to obtain information about the providers and facilities that care for attributed patients that utilize home health.

If you are currently a member and interested in how CareJourney can help you gain insights into home health care, please reach out to your Member Services representative for more information. If you are not a CareJourney member, please email us at jumpstart@carejourney.com, or you can learn more by requesting a meeting below.

- Medicare and Home Health Care. (2003, April). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Downloads/HHQIHHBenefits.pdf

- Van Houtven, C. H., & Dawson, W. D. (2020, October 21). Medicare and Home Health: Taking Stock in the COVID-19 Era. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/medicare-home-health-taking-stock-covid-19-era

- Cornwell, T. (2019, October 08). Home-Based Primary Care: How the Modern Day “House Call” Improves Outcomes, Reduces Costs, and Provides Care Where It’s Most Often Needed. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191003.276602/full/#:~:text=Home%20health%20care%20is%20also,patient%20as%20long%20as%20needed

- Does Medicare cover home health services? (2014, January 1). Retrieved April 02, 2021, from https://www.aarp.org/health/medicare-qa-tool/does-medicare-cover-home-healthcare

- Joynt, K. E., Figueroa, J. F., Beaulieu, N., Wild, R. C., Orav, E. J., & Jha, A. K. (2016, December 01). Segmenting high-cost Medicare patients into potentially actionable cohorts. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213076416302287?via%3Dihub

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2020, May 22). Retrieved April 23, 2021, from https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/home-health

- Texas Department of State Health Services. (2021, April 22). Health Professional Shortage Area Designation. Retrieved April 23, 2021, from https://www.dshs.state.tx.us/tpco/HPSADesignation

- Independence at Home Demonstration. (2020, August 25). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/independence-at-home

- “Hospital at Home” Programs Improve Outcomes, Lower Costs But Face Resistance from Providers and Payers. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/hospital-home-programs-improve-outcomes-lower-costs-face-resistance

- Hospital at Home. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home

- Hospital care is not always best for older adults. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from http://www.hospitalathome.org/about-us/overview.php